When the Beginning Hour demo for Resident Evil 7 first launched back in June of last year, the first words to greet us carried with them the weight of a twenty-year-old franchise: “Welcome home.” They were carved into the damp, tea-stained wallpaper of a dilapidated hall, splintering wooden slats exposed behind crumbling plaster. It was a foreboding image, but it was a relief, too. We had been away for too long.

The Resident Evil franchise is one that’s at its most effective when it’s wrapped up in a single, labyrinthine location. It doesn’t matter what form this takes – a mansion, a police station, a moving train – the trappings tell us what we need to know. The Spencer Mansion from the very first Resident Evil was an ornate prison. The clatter of boots on slick marble echoed off baroque walls; lavish, overwrought stonework swirled above fireplaces. Who lived here? It was isolated from the world and seemingly from time. Resident Evil 2’s police station worked in a similar fashion. Bullet casings strewn across floors, the jumble of overturned furniture, the thick emulsion of blood smeared across walls – this one wasn’t a story of isolation; it was one of abandonment, of frantic desertion. When you are mired in a setting, these intimacies bury themselves in your mind far more deeply than when you’re free to come and go. Revisiting rooms again and again imprints them on our minds, and we become fused to a place.

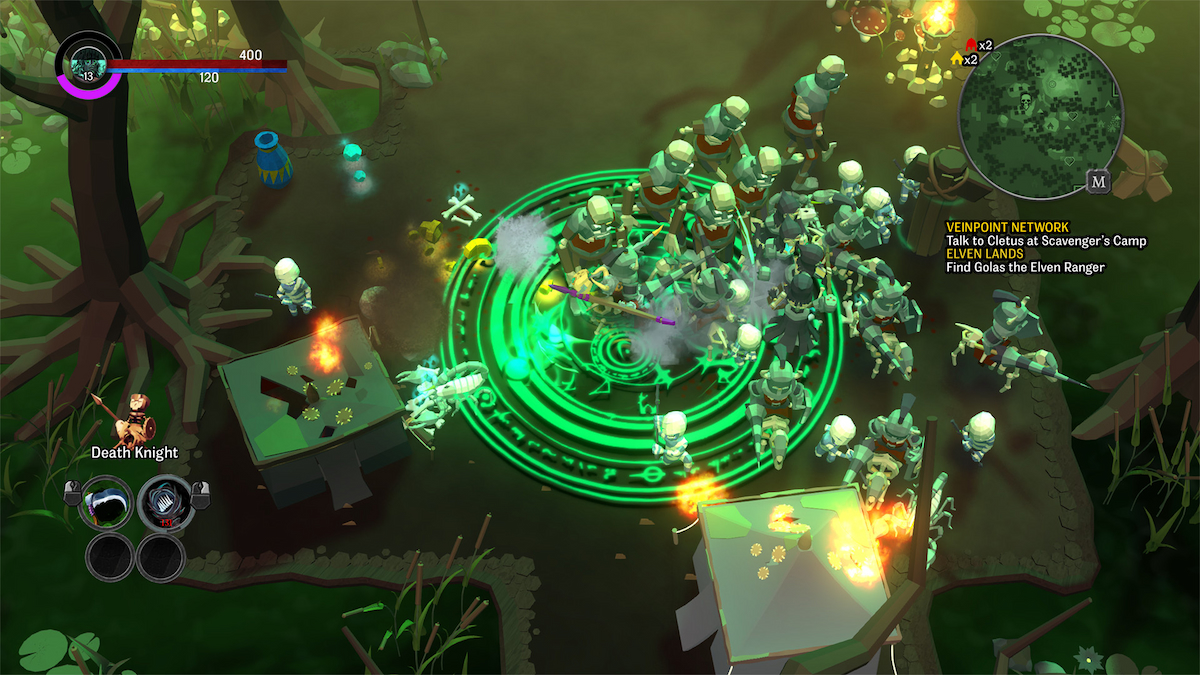

If you look at Resident Evil 3 and 4, you can see a pattern emerging. The move to more crowded, open areas carries not quite fear, but panic. The inner city spaces of Resident Evil 3 are rotten with urban decay, overflowing with shuffling corpses. Though you visit the same police station from 2, you aren’t there for long; the game keeps you moving from one area to the next and has a less vivid sense of place for it. In Resident Evil 4, you’re confronted with a sprawling village – its edges envelop you and you’re surrounded. These games become more about thinking on your feet, about crowd control, and manipulating space to gain a vantage over the horde. It was more about stress than fear in both of these games, and even in 3 where you are hunted by the Nemesis, it’s panic that takes hold as you frantically choose between fight or flight. These open spaces have just as much to do with the series’ mutation as the plentiful ammo and boulder-punching ever did.

While Resident Evil 4 was able to irrigate the flow of action into enclosed spaces, and you could just about feel the twinges of fear in the quiet moments between fire fights, the fifth and sixth games in the series smashed the door down into full-on action territory. It was no surprise that Capcom, when deciding to hit the reset button, shifted back to a domestic setting for Resident Evil 7.

And so after pushing through the swelter of a backwater Louisiana swamp, you see the Baker family plantation emerge from the haze, a vision of Southern Gothic. That cold feeling in the pit of your stomach when you saw the house – that’s what we’d been missing all this time. It’s here that the difference between fear and panic becomes clear. Panic is temporary; fear is enduring. When you are enclosed in a structure, there is inevitability to the proceedings. Whatever happens will happen here. Movement is constricted; time seems to slow. But what happens in these moments endures far more than any fleeting panic ever will. There are a few reasons for this. Let’s talk about doors.

Resident Evil has a storied romance with doors. Those indulgent animations made you hold your breath at the resounding creak; moving through the frame, you were swallowed by darkness. These intermissions would distort the temporal flow. A long hall of doors felt that much longer for the time spent in fully exploring it. Each room was contained and isolated, yet inextricably part of a larger whole. A lot of survival horror has its innovation married to limitation. These door animations are the result of needing to hide a loading screen; Silent Hill’s iconic fog is an elegant way of disguising its limited draw distance. Capcom turned a weakness into one of the series’ most artistic touches – it speaks volumes that for Resident Evil: Deadly Silence on the Nintendo DS, these sequences were no longer necessary but remained anyway, giving players the choice to skip them or not.

This distortion of time and space lengthens your anticipation of what lies behind these doors, and fear of the unknown is always more enduring – how many times have horror movies ceased to be scary when they reveal their monsters? What this means is that as you explore, you feel a distinct push-and-pull. Your compulsion to surge forward is met with the churning apprehension you feel at every door.

Resident Evil 7 has a renewed love of them. Gone are the cutaways; you are free to explore seamlessly. Only now the temporal flow is in your hands. Do you tentatively push it ajar and see what you can glimpse in the gap? Do you brashly boot it open? Or ease it open with a soft push? It’s a thrilling kind of theater, and one which you imprint your own psyche onto.

Your psyche is important – an intricate building is inherently psychological and breeds a specific strain of horror. In her excellent review of the game, Zhiqing noted, “The Resident Evil games have always been about facing and overcoming fears, eventually giving way to a brighter and hopeful future.” This is, of course, true in a literal sense; however, it begins to take on new meaning in a single, stagnant setting. As you advance through the house, all of your actions – the way you move, the way you open doors, the way you train your gun down hallways – turn the house into an analogue of your mind: every tangled corridor a synapse, every lurking monstrosity a personal demon. Most enemies – with some famous and horrifying exceptions – can be contained in rooms; unable to open doors, they could be trapped, the act of frantic retreat became like an act of repression.

In the wake of Resident Evil’s sojourn into action, a number of horror titles picked up this torch. In Anatomy, independent developer Kitty Horrorshow transfigured a house to resemble the human body: the living room was the beating heart, the master bedroom the dreaming brain. In the Justine DLC for Amnesia, the dungeon you were locked in echoed the Freudian structure of the titular villain’s mind – festering below an upper-class mansion, just as malicious, psychopathic intent festered under her cool, clipped outward manner.

Overcoming these fears in a psychological sense means overcoming the geography of the structure. It’s no coincidence that the Resident Evil games usually have you confront what lies below – the Spencer Mansion’s subterranean laboratories, the salt mines below the Baker plantation – before leading you back up to the surface and usually to a roof. As Zhiqing points out, “There’s usually a chopper and a beautiful sunrise involved, too.” These moments are ones of catharsis: after delving into the recesses of our mind, we rise to the surface renewed, hopeful.

Survival horror, as we know it now, grew from Resident Evil. Over the years, as mainstream gaming demanded a more action-oriented approach and Capcom masterfully mutated its series to suit changing tastes, it created some incredible games. But I’m betting that a lot of you felt that same sigh of relief that I did in June last year when you saw that wallpaper. It feels good to be home again.

Updated: Feb 13, 2017 08:49 am