The World of Vetrall: Immersion, Lore, Game Design

After several years of development, Seven: The Days Long Gone is closing in on its launch day — it was announced last week that the open-world role-playing game will be launching Dec. 1 for PC via Steam and GoG.

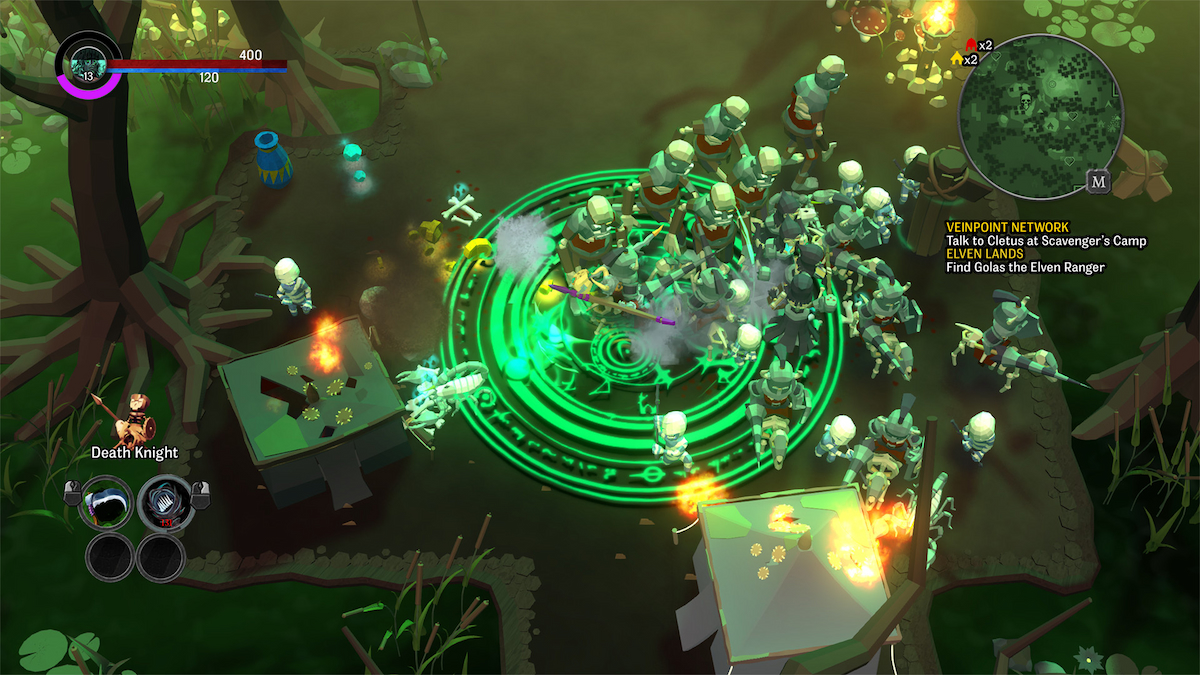

The collaborative effort between studios IMGN. PRO and Fool’s Theory has attracted attention for its unusual blend of exploration, parkour, and stealth played from an isometric perspective. And not least because the latter team is largely comprised of former CD Projekt RED staff who opted to leave the studio following the release of The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt. Seven: The Days Long Gone is their debut title, the brainchild of two teams newly armed with the creative freedom to imagine their own fantasy epic.

Twinfinite had the chance to speak with the game’s director, Jakub Rokosz (Fool’s Theory), and its composer, Marcin Przybyłowicz, to find out a bit more about the world of Seven and the depth we can expect from its mechanics and design. We were also keen to better understand the inception of the studio, and hear Jakub’s thoughts on trading AAA for independent development.

Alex Gibson from Twinfinite: CRPGs have been using the isometric perspective for years, and there are well-established franchises that have continued this trend in modern gaming. Do you feel that the parkour and stealth elements to Seven’s gameplay are enough to make it stand apart from popular titles such as Divinity Original Sin and Diablo III?

Jakub Rokosz: We understand that Seven will be compared to games like that because of its isometric perspective, but we believe that our game is original enough to stand out from the crowd. We always wanted to respect the isometric RPGs that we’re so fond of, but see Seven as being a breath of fresh air within the genre. The main way we do this is by giving the player freedom of movement and choice in the game world.

Twinfinite: When conceptualizing Seven, were mechanics like stealth and parkour part of a brainstorming process specific to this project or are these gameplay mechanics you’ve always wanted to see incorporated into a role-playing game?

Rokosz: Yes and no. Parkour was always planned, and stealth naturally emerged from it, as well as the 360-degree rotatable camera, but all of those features were more or less means to achieve the goal we set before ourselves. Our main focus was to give freedom of movement to the player, so most importantly: no invisible walls, no place unclimbable. I always hated the feeling of being stuck to the ground in old RPGs, or seeing an awesome vista while progressing through hell in Diablo, but being unable to go there.

For me, the most irritating feeling I experienced while playing an RPG was encountering a decoration made of millions of gold coins and treasure chests, but that are only static objects; you could only loot the single chest that was in the “playable zone.” While making Seven, it wasn’t really a matter of incorporating parkour into the genre but giving the player the freedom to do, loot, and explore whatever areas they want. Parkour was the best means of doing that.

Twinfinite: Seven’s aesthetic catches the eye for its blend of sci-fi and fantasy. In the lore of Seven’s world, is there a conflict between technology and magic that we can expect to play a central role in the narrative?

Rokosz: I don’t want to spoil too much of Seven’s lore and world beliefs, but I guess I can say that the distinction is blurred. I recall that the quote from Arthur C. Clarke – “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” – really impacted my ideas while designing the core fundamentals of the Vetrall Empire.

Twinfinite: The Vetrall Empire seems like a bit of a grim place overall. Is there a brighter side to Seven or is the tone of this game along the lines of cyberpunk and dystopia throughout?

Rokosz: Yes, the Vetrall Empire isn’t a nice place to live for many, but like in all dark places a little light of hope can be found. And we do find it – in the way a husband and soon-to-be father loves his wife. In good deeds that random strangers are prepared to do, and in the selfless acts that you as a player can choose to do to receive a kind word from a poor soul. At the same time, you can be as grim as they come: backstab everyone, steal, cheat, and lie. Like in the real world, it all depends on what you make of the life you are given.

Life in the empire is also very different depending on social status. Wealthy, well-connected people can live in luxury, even on the prison island of Peh, whilst downtrodden unfortunates struggle to survive. Not all of the oppressed residents of the empire are resigned to their fate, however; some use black humor as a way of coping with their situation.

Twinfinite: The production quality of the game looks impressive from what we’ve seen so far, but we haven’t heard much yet about voice acting in the game. To what extent, if any, can we expect to hear voice acting in Seven?

Rokosz: We will have English voice-overs for all of the quests and quest-related content. The only things that will not be voiced are the descriptions and journals you will be accessing from the menu, and some random chats from the passers-by.

Twinfinite: I couldn’t help but notice the game’s score has been composed by Marcin Przybyłowicz — whose previous work includes The Witcher 3. What role does the score play in bringing to life world of Seven and relaying the tone of its story?

Rokosz: I could answer that, but I would rather give Marcin the opportunity to voice his thoughts. Marcin – take it away:

Marcin Przybyłowicz: Hi! Actually, quite significant I think. Since its inception, Seven was always appealing to me with its suggestive vision. It’s not common to work on a project that allows the composer to have that much creative freedom. A carte blanche really. One of the examples of such freedom is the overall sound palette we chose for this project. We started with a simple idea – it’s a “beyond-apocalypse” setting, so we thought Peh’s citizens would use all the scrap they can scavenge to build anything, including instruments they’d use for their own amusement. Why not try to record such instruments in real life and make them one of the pillars of Seven’s sound?

We reached out to Paweł Romańczuk, leader of the Małe Instrumenty project – old instruments’ collector, and a constructor. Paweł let us explore his workshop and record some of his most significant artifacts, including Bucket Bass (made out of a metal bucket and one bass string), Cardboard Cello (made out of an office chair leg, cardboard tube, cello strings and guitar pickups), authentic, 100-years-old Stroh Violin, and so on. There was some really exceptional stuff there; very raw and authentic in its sound.

The other pillar of Seven’s sound are elements of the western genre. For me, the reality of the Vetrall Empire has much of a Wild West vibe, so I wanted to pour some of it into the music as well. That’s why we have lots of sounds recorded on guitars – resonator guitar, cigar box guitar, twelve-string guitar, electric guitars, etc.

I think we did something special here, to make this grim reality of Seven’s world breathe and have its own voice. I really hope our audience will fall in love with it the same way I did!

The Origins of the Project and Leaving AAA Development

Twinfinite: I understand that some members of your team worked on a certain well-known RPG out of Poland before starting work on Seven. What has the transition been like from a large AAA studio to a smaller independent team? Have your experiences working in those larger studios shaped how you approach game design and implement these ideas or is it a case of tearing up the rule book and doing things your own way?

Rokosz: It has been an interesting experience for sure. For me, personally, it was the biggest challenge of my life as I went from working in a team to leading a team of 20 people. The transition was rough, stressful and full of surprises, but you cannot really expect to achieve anything in life without leaving your comfort zone.

As for the impact that working in a large AAA studio had on our current work, it definitely helped to work on a big RPG, but that’s not really the most important part – it’s the people whom we’ve worked with. In the years before starting to work on Seven, we had the opportunity to work with some of the best experts in their respective fields, and that environment made a huge impact on how we approach game design. The same applies to working in a smaller studio now – it’s the people (once again) who make Seven work. It’s this small team of people who think and feel in a similar way; small enough for every member to have a real impact on the design and implementation process.

It’s not really a matter of “tearing up the rule book” and saying “I will do this my way now,” because I think that every game development process that aims to create something original is starting from the point where some rules have to be abandoned. In my opinion, it’s the people you do this with that help you navigate the uncertain development paths of your future game-to-be.

Twinfinite: Could you say that you would recommend swapping the intensity of a large studio for the challenges of forging your own path in a smaller team?

Rokosz: It depends on what you are currently looking for in life. I remember that one of my earliest frustrations when starting to develop games was that I didn’t understand so much: how some systems are done, how things are being produced. So I decided to understand it all – and for me working on a big franchise was great, because I had 200 smart people around me that I could pester without end with my weird questions, or brainstorm with at any given time of day and night.

On the other hand, you might have a hard time getting some of your ideas through, especially if you’re in a junior position. Just because there are so many people involved, and their vision might be different altogether.

Different game studios have different work cultures, but it’s a fact that happens everywhere (not only in video game development). It wasn’t really my case during my time with CDP (as my lead would always hear me out, probably because I was shouting so loud 😛 ) but it does happen, and it tends to happen less in the smaller teams.

I decided to try and do something with a smaller team because I wanted to finally get this project (that has been sitting in my head for ages now) out to the world, and it was the best way to do it.

Updated: Oct 12, 2017 04:52 am