During a panel at Reboot Develop in Reboot Develop 2019 in Dubrovnik, Croatia, former Uncharted Creative Director Amy Hennig talked about her vision for the future of gaming.

Hennig mentioned that at the moment she is as a personal crossroads as she’s deciding where she wants to land next following her departure from Electronic Arts.

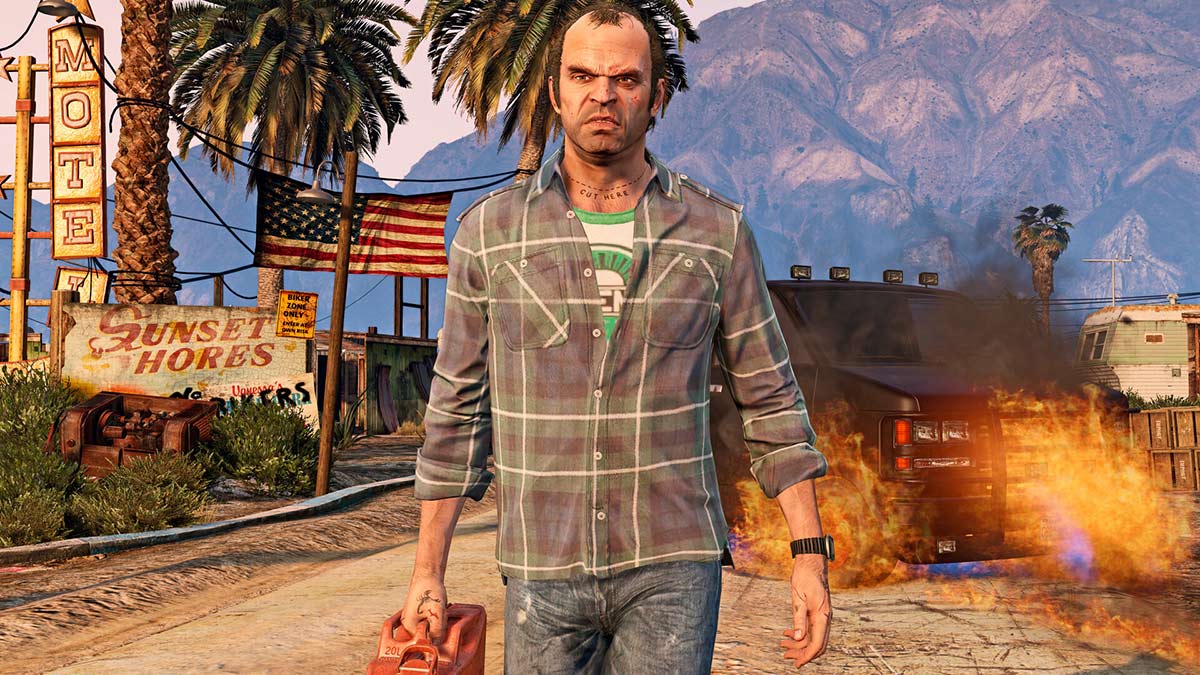

She then went on to explain that Uncharted 4: a Thief’s End was double the size compared to the first game, and the same goes for the new God of War against the original game, or Mavel’s Spider-Man in comparison to a game by Insomiac from a decade ago. Development times and team sizes have also doubled or more. On the other hand, the price point of games has not changed.

According to Hennig, some of the pressures and controversies that happen within the gaming industry stem from this: the scope of games has increased by prices have remained the same, and nobody wants them to go up. There is a reason why games have been the same price for a long time: if it goes beyond what we have, it feels like a much bigger investment.

Yet, that’s also why a lot of things happen around games-as-a-service, trying to keep people in a game’s ecosystem while continually monetizing them. The same goes for the rise of loot boxes. On the other hand, there is what Hennig calls the “GameStop phenomenon”: if developers made a finite game, it was perceived by players as a possible rental or something to purchase pre-owned.

Publishers responded by trying to create value or even just the illusion of it, and that’s also why we see many games with multiplayer tacked on. If there is more to the game, it may encourage players not to trade it in and keep it on their shelves.

Henning then argued that the current situation in terms of development cost and complexity is “sort of self-inflicted.” Developers have shifted from finite stories to games that just don’t end, and that’s a “very weird place to be” for her as a storyteller, as a story is by definition finite. It has landmarks and a deliberate end.

On top of them, not only finite games aren’t made often nowadays, but when they are, they can be 20, 30, or 40 hours, and the common wisdom is that players don’t finish them. That is “kind of upsetting.”

That being said, this doesn’t mean that it’s the players’ fault. Henning as a gamer herself is drawn by today’s games, but she knows that she won’t have the time to finish them. While gamers often feel intimidated by admitting that they may be a bit disenfranchised for fear of losing their gamer cred, Hennig’s whole circle of gamers privately admits that they feel “sort of overwhelmed by their own hobby.”

She also doesn’t mean that those kinds of games shouldn’t be made, but she feels that mainstream AAA developers aren’t making the “whole spectrum of games” that they could. Everything doubles down on mega-blockbusters, which are much more demanding than they used to be in terms of commitment, resources, time, and money. They’re “all Hail Marys.”

As a gamer, Hennig finds herself seeking the finite experiences that can be found on Steam and similar spaces, and she finds them the most rewarding. Despite being “dumbstruck” with admiration for what the big games like God of War and Marvel’s Spider-Man achieve, she feels that she’ll never get to experience them fully. As a creator, she thinks about how that would make her feel if she had made them and people didn’t finish them.

Conversely, while the gaming industry tries to make bigger games that never end, traditional linear media like film studios are trying to make more bite-sized content. There is so much competing for the audience’s attention, that many are trying to create media that is more digestible.

Each of Uncharted’s chapter was sized pretty much like a television episode, and while that wasn’t intentional, it created an opportunity for players to digest them and then take breaks or binge if they so wished.

Henning believes that the line between interactive media (games) and linear media (tv and film) is going to be blurred, so she is wondering where we’ll land between these two poles.

She also believes in authored stories with clear anchor points, payoffs, and endings and the player is given agency between those points. Things like Bandersnatch feel backward because we’re watching the parts that we’d normally be playing, and we’re altering the parts that are normally “confidently and intentionally authored.”

According to her, if we agree that the rapid adoption of 5G is inevitable and that it means that real-time gameplay streaming is inevitable (and we can debate about how many years that’s going to take), it will potentially change games, the business models, the players in the space, the content that can be created, and the audience. That’s why she likes the fact that Bandersnatch exists because it’s the best model of “frictionlessly easing non-gamers into interactive content.”

There’s no extra cost because it’s part of a subscription you already have and you don’t need to pick up a controller or being intimidated by that, which according to Hennig is a “huge friction point.”

She expects gaming to be heading towards a major change in both exciting and worrisome ways. There will be things that will have to be overcome, including how we define our own hobby, including whether it’s something for an elite as opposed to everyone.

There is a lot of debate around accessibility and difficulty, and whether gaming experiences should be made accessible to everyone. Hennig believes that it’s important to separate the question of accessibility (making it so that people with diverse needs are able to play the games) and the question of difficulty focused on whether by dumbing down the game to include more people, developers would be altering the core experience.

Hennig is of two minds about that, but thinking about this potential new marketplace, she believes that we have to be open to the idea of welcoming new people into the hobby.

All major film studios now have an interactive division, and they’re going to be on this. While they may be more adept in storytelling and character development, they don’t understand real-time gameplay at all and interactivity.

Hennig argues that those developers who can operate at a high-level in story, real-time, and interactivity have a great opportunity to define that space for a wider audience. If they don’t do it, other people are going to. Developers shouldn’t be saying “here are the games we’ve been making, now become a gamer” but should instead make experiences crafted for that wider audience.

This is happening more in the indie game space, with titles that aren’t about all the factors that prove intimidating for a mainstream audience, like mastering difficulty and “beating” the game (Hennig mentioned that games are the only kind of media in which you talk about “Beating.” You don’t “Beat” a book.).

Games have been traditionally about competition, but Hennig thinks that we should widen the way of thinking about them as experiences, and that doesn’t require “difficulty, competition, mastery, fail states, and setbacks.” She clarified once more that she is not trying to be dogmatic and she isn’t saying that those games shouldn’t be made, but it’s more about widening the sphere.

Games that are about competition, difficulty, and mastery should still exist, but that makes non-accessible to a wider audience. She doesn’t believe that the exclusive “git gud” attitude is healthy. Developers should be open to the idea of creating content that isn’t about difficulty, but it’s about a journey and the experience.

She believes that with games like Uncharted we’re already 90% there, but developers need to still adjust a little bit to make content that is still like existing games, but for an audience who wouldn’t necessarily buy a PS4 and “pick up that 15-plus-button controller.”

While there is an aspect of the gaming space that wants to stay that way and it’s not going to go away, it’s more of a question about widening the horizon and take what developers know how to do and be first to market where others are going to come in and try to clumsily do something.

About announcements like Google Stadia, Hennig believes that it’s amazing to see real-time content streamed directly into everybody’s homes and devices just like TV and film, and that’s mindblowing. Yet, it’s a bit weird because everything is simply justified as game streaming, with the same games that we have now, and that turns out to be just an invisible console. It doesn’t really involve a bigger audience but targets simply the same people who are already buying hardware.

While that comes with benefits, it’s very limited thinking. Google and others are talking about how their services can reach many more people, but the next beat of that conversation should be about content, instead of being about just having access to the same games. If that new audience was into those games, they would already purchase them through existing channels.

On the other hand, games like Florence or Return of the Obra Dinn would be appealing to new audiences because they don’t have fail states, but they have zero discoverability for that audience. If you don’t know where to search and you’re not already into those games, you wouldn’t even know about it.

It’s critical to find out how these streaming services can cater to new audiences as well as existing gamers. Games like Uncharted, Until Dawn, or Detroit: Become Human are able to invest non-gamers as well as gamers and their families. Non-gamers aren’t just watching a TV show, but they are interacting and investing with elements like mystery, discovery, and puzzles, as well as the stories and characters that make those engaging.

Both Uncharted in the adventure space and Until Dawn in the horror space had the benefit of leaning onto “well-loved tropes,” which Hennig believes is inclusive for a wider audience. When she sees that audience involved with those games she asks herself “why not designing that intentional rather than just stumbling into it” and “why not making content for those people instead of putting it behind gates.”

While controllers are well-crafted for gamers, they’re an “absolute non-starter” for that audience. You can’t even just say “let’s just use two buttons” because the device itself is intimidating. Smartphones can work like a Trojan Horse, so that should be used as an input device for the new audience. On top of that, since the idea is easing them into the experience, the industry shouldn’t throw obstacles like mastery and difficulty at them.

Henning concluded by clarifying that nothing of what she says is a critique of what the industry currently does, but she’s just looking at what it’ll have to do to reach a wider audience. She believes that this is additive to catering to hardcore gamers, rather than an alternative. After all, games are a big piece of people’s identity, and developers have to be sensitive about that as well.

Updated: Apr 13, 2019 05:50 pm