[Warning: this article contains story spoilers for Acts 1 and 2 of Broken Age]

Personally, I’m not a fan of kids and teenagers. I’ve been through my rebellious teenage phase and I would not want to deal with that again. But if I did ever raise a kid up to her adolescence, I’d make sure she grows up with a happy childhood, stays safe, eats her veggies, and kicks all the other kids’ asses in videogames. That’s what a responsible parent should do, right? Not so in Broken Age.

No. In Broken Age, it’s a great honor to have your 14 year-old daughters get picked to be a sacrifice to a legendary monster in exchange for the ensured protection of your village. Your family members prepare cakes and cupcakes for you, they congratulate you, and they tell you how lucky you are to even be considered by the dreamy Mog Chothra. In Broken Age, we learn that it’s the parent’s responsibility to make sure your daughter’s all dolled up and ready to get eaten by a monster so that she can protect us. The parents don’t safeguard their children in this instance; the kids are the ones who take up the mantle of saving their elders.

It is ironic when Vella’s family tells her she was picked for the Maiden’s Feast because she represents the best qualities of her village. Her fierce determination and desire to break the mold – both of which would be seen as admirable traits in our society – are met with patronizing smiles from her villagers and fellow maidens. Rather than protecting Vella, her ‘best qualities’ are used as the reason for her sacrifice to the great Mog Chothra.

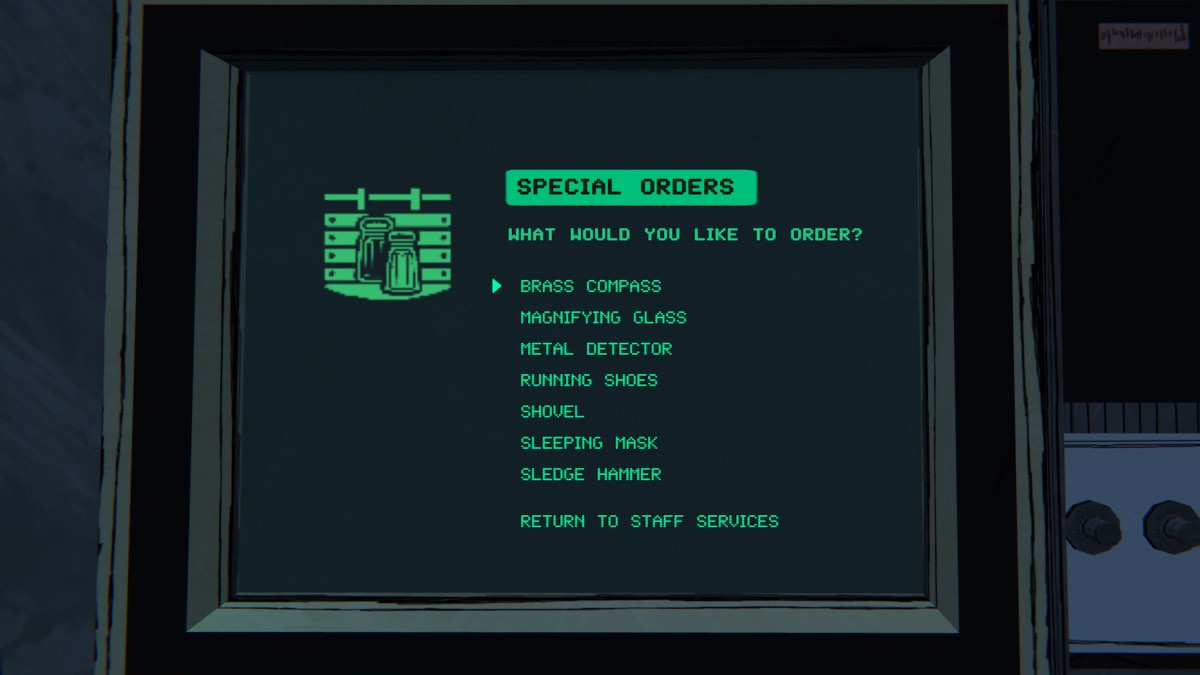

When the parental figures of Broken Age aren’t offering their kids up as sacrifices, they’re smothering them with their overwhelming presence and thus never giving them the chance to grow up. In Shay’s half of the game, his mother is an omniscient presence who has eyes and hands everywhere on the Bassinostra. Shay isn’t allowed to explore the ‘universe’ by himself; he isn’t even allowed to bathe himself. The computer manufactures rescue missions for him to undertake where he rescues his Yarn Pals from ice-cream avalanches and hug attacks.

The growing pains of children and millennials are consistently conveyed through the game’s subtleties – the talking knife’s cheeky and uncomfortable quip of “Cutting is always worth it” comes to mind – and the game quietly reminds us that growing up is never easy. We often hear about how the teenage years are the best in our lives, but hardly anyone seems to want to remember the hardships that came with them.

Tim Schafer’s take on childhood in Broken Age is pretty warped. We have kids who are forced to grow up too fast, and we have kids who never get the opportunity to see the real world with their own eyes. While Schafer’s view on childhood and the theme of growing up is an overall positive one, the message that he delivers behind the carefree, fairytale-like quality of his story is indisputable: parents are just as broken as their children. Just like us, they are tricked, misled, and in their confusion they inadvertently end up breaking their own children as well. We like to believe that we treat our kids well and that everything we do is for their wellbeing, but Broken Age flips this idea on its head and tells us that we don’t really know any better either.

When Vella and Shay do eventually have the proverbial blindfolds removed from their eyes, and they finally see the world for what it really is, the truth thrusts them into a reality where they learn that their parents have been wrong this entire time. But things aren’t all bad; Broken Age reassures its audience by showing us that we, too, can channel our childhood pain into strengths that harden us for the challenges we face in adulthood.

Shay, who has become so used to the smothering hugs he’s received from his Yarn Pals, hardly bats an eye when a boa constrictor attempts to squeeze him to death. And it is fitting that Vella, who has been forced into the role of the caretaker and savior, should be the one to ultimately save the world by beating up the bad guys and firing her death rays. These in-game examples fall a little bit on the silly side, of course, but are nonetheless effective metaphors for learning from past hardships and applying them in new situations.

It seems to be a new trend for videogames to explore the theme of growing up and the relationships between kids and parents; Life Is Strange (hella hella hella), The Last of Us, and The Walking Dead come to mind. In all of these games, we experience a struggle with the protagonist and watch as they (usually) grow into self-possessed young adults who become better equipped to deal with obstacles in life. Broken Age deviates from that standard formula just a tad. In Schafer’s game, there is a larger emphasis on the idea that the parents, who the kids trust and look to for advice, are often just as lost as the young ones.

We like to think that with age comes experience, and that makes us qualified to tell the next generation what’s best for them. Broken Age challenges that assumption and poses a question to the adults: are we really sure that we treat our children well?

Updated: May 4, 2015 07:29 am