*This article contains spoilers for Starfield’s entire main story*

I know I’m not alone in spending an unhealthy amount of time daydreaming about just what would happen if we ever discovered that we weren’t alone in the universe. First contact narratives are one of my favorites in science fiction, and the promise of traveling the stars to seek out alien life was one of the things which had me most excited about playing Starfield.

Even before the game launched, we knew that we were going to be chasing down artifacts that were obviously of alien origin. It seemed safe to assume that at some point during the game, you’d end up coming face to face with their creators.

As you approach the game’s final act, this reveal seems imminent; only for the would-be aliens to reveal themselves as universe-hopping humans. Because, of course, Starfield has to be yet another multiverse story, fantasy writing’s current obsession.

Reader, my disappointment at this revelation was immeasurable. I audibly groaned and rolled my eyes, and my hopes of seeing even one scene that encapsulates the wonder inherent to sci-fi storytelling felt dashed.

But just as I had all but written the game’s story off, one specific section had me reeled back in. When just a few hours earlier I figured I would slog through the rest of the game just to see it through, here I was, sometime after midnight, unable to tear myself away from the game.

Following hours of traipsing across barren landscapes and the occasional future city, the mission in question dragged me to Earth’s moon. More importantly, it took me back to Earth’s past, or at least had me exploring what had happened in its past.

I was ready for this. I love the game’s NASA punk aesthetic. But while that look rooted it to our real-world forays into space exploration, I had until this point found the game veering closer to space opera than the grounded or ‘hard’ science fiction that I had hoped for.

That’s understandable. In wanting to deliver a game where you could explore the cosmos, Bethesda naturally had to skip the ‘grand exploration’ phase of human space colonization. Space opera also presents more opportunities for combat, romancing, and all that other essential RPG stuff.

Barring the lack of other intelligent alien species, Starfield also does a good job of bringing the Star Trek fantasy to life. As everybody knows however, the best episodes of Star Trek are often the ones that see the Enterprise crew travelling back to Earth’s past — to the world we recognize, along with all its failings and small-minded naiveite.

So there we are, on the moon. Poking around a deserted space base from a time before we had conquered the stars. Reading through the logs of the crew stationed here, it quickly becomes apparent that there was more going on at the base than what they’d signed up for. A mystery reveals itself, and the answers to our questions lie on Earth.

We’ve already learned by this point, that Starfield’s Earth has long since become an uninhabitable dustbowl. We, and the rest of the galaxy, assume this is down to some kind of climate crisis. Thankfully for us, the one landmark that appears to still be somewhat intact is a NASA launchpad and visitor center.

Where we’ve spent the game up until this point seeking out abandoned monuments built by another mysterious species, we now find ourselves in one built by our own hands. Inside the building, things are eerily untouched from the ravages of the outside world.

Relics of our spacefaring past — real ones, such as the Mars Rover and the Mercury spacesuit – are displayed as museum attractions. There are no people though; just structural creaks and howling winds to pierce the silence.

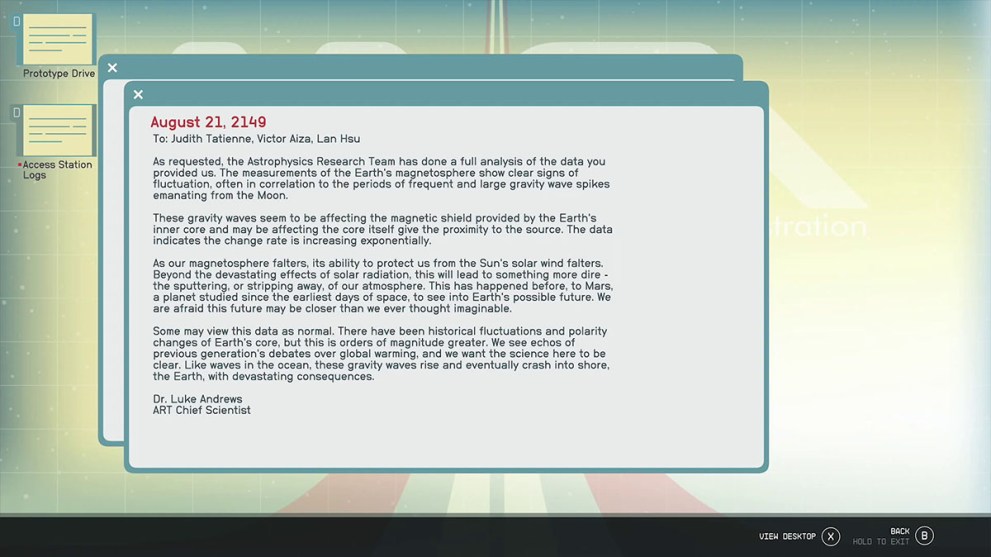

As we power up the computer terminal and begin searching through the logs stored on them, the truth of Earth’s fate reveals itself.

If we were to one day switch on our televisions or open the internet, or even look outside and stare up at the sky, to be met with the news that we are not alone, it would doubtless be one of life’s out-of-body moments. The kind we’ve all experienced before, usually when something tragic and unexpected happens that forces us to re-examine our perception of reality.

Standing in front of that computer terminal, reading these emails as the characters from Earth’s past come to realize the enormity of their discovery — of the consequences that it will have for humanity —gave me that same sense of disassociation that I just described. I felt the blood run out of my body, and the hairs on my arms stand on end.

This moment came as a surprise following all the multiverse mumbo jumbo (which it would quickly revert to once we departed Earth). As I stepped away from the console and took a moment to comprehend the reaction I’d just had, I realized that, like the multiverse stuff, the actual contents of the emails were nothing all that original.

The discovery of an alien artifact on the moon is ripped straight from 2001. The means to create the Grav Drive necessary to travel the stars being gifted to us by an alien species is exactly what happens in Contact. The central moral dilemma, which essentially boils down to whether the continued pursuit of progress is worth the cost it extols on the planet, is timely, but Starfield offers no new answers, instead asking us to choose which side we fall on.

What affected me could neither be contributed to the way the events was presented. In regular Bethesda fashion, we experience all of Starfield’s story through our own character’s eyes. There’s no flashy cinematics, and this sequence in particular was conveyed mainly through that most tired of game mechanics, the audio and text log.

No, what made this moment hit home was simply the medium through which it was delivered. After spending some 20 hours over the past few days walking around in the moon boots of my avatar, I was absolutely immersed in Starfield’s universe by this point, and the revelation felt all the more real as a result.

Granted, I’ve been profoundly affected by many great works of science fiction before, from the cinematic splendor of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey to Star Trek’s voyages aboard the Enterprise. Some of my all-time favorite novels are Olaf Stapledon’s Last and First Men and Star Maker, 2 seminal texts which share much in common with Starfield’s central themes of space colonization and alternate universes. They’ve made me feel hopeful, filled me with cosmic terror, and offered a taste of the transcendent.

But this was something quite different. Something that made me react in a way that felt primal. I’m convinced that video games are the only medium that could have made me feel like that.

More than at any other point in the game, the NASA sequence is the moment where all of Bethesda’s attention to environmental detail comes together to create something that feels cohesive. It’s curious that there are also so many essential gameplay elements left absent from this mission. Save your companion, there are no NPCs to interact with, and thus, no branching dialogue choices to be made. Combat is restricted to disabling turrets until you have a few run-ins with Starborn towards the end of the mission.

With that being said, would Starfield have worked better had it just been an adventure game or a walking sim? I’m not sure that the connection to my character would’ve been as strong had I not been controlling him through all those previous shoot-outs with space pirates, or even all those hours spent fussing over petty things like inventory management.

There are simply too many moving parts at play for Bethesda’s game to not feel a little janky and a little scattershot at times. But when it allows itself to strip away some of its looser parts to become a necessarily tighter, more restrictive experience as it does on Earth, Starfield excels because of all that ‘extra stuff’ you’ve been doing before then, not despite it.

As all that stuff fell away (without me having realized it at the time), I was finally able to become fully immersed in my character and to feel the weight of this extraordinary moment first-hand.

It’s too early to say whether this alone can elevate Starfield to the hallowed pantheon of essential sci-fi. The reasons that make this 1-hour long mission so effective are the same ones that drag the rest of the game down. The plot is simply too fantastical, the events too ‘out-there’ to not feel flattened by the perma-first-person, close-up framing of static characters doing little more than talking at you.

Still, we’ll always have Earth, and that brief moment Starfield almost made me feel like we really had made contact.

Updated: Sep 15, 2023 07:40 am