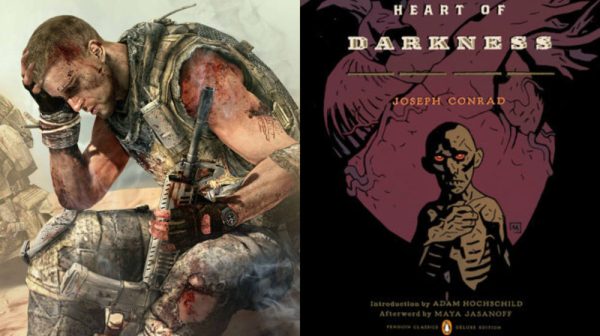

Spec Ops: The Line – Apocalypse Now

Specs Ops: The Line was one of the last generation’s single-player gems, but poor sales mean that tragically few people have ever actually experienced what might be one of the best stories in modern gaming. Following his experiences working at 2K Interactive and helping to write games such as BioShock 2 and Mafia II, Spec Ops: The Line was Walt Williams’ first gig as a full narrative lead, and boy did he nail it.

The story of Specs Ops: The Line follows Martin Walker and his squad of American Delta Force soldiers as they disobey orders in an attempt to neutralize a rogue US commander, John Konrad. Hunting the frenzied Konrad and his mutinous platoon amid the sand-covered Dubai on the brink of collapse, it quickly becomes apparent that the horrors of war have turned Konrad into a frenzied lunatic. But things aren’t quite what they seem; there’s one almighty twist at its conclusion that throws everything on its head, which we won’t spoil here.

For anybody that has played it, the parallels with Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness are obvious. The rebel commander (whose name is rather blatantly a nod of the hat to Conrad), the psychological effects of war’s most gruesome realities, and erosion of the chain of command: all themes that comprise the narrative thrust of Specs Ops: The Line’s plot, and all lifted from that seminal piece of literature. Walt Williams wasn’t shy to explain the inspiration in his book, Significant Zero, as well as citing other works such as Platoon and Full Metal Jacket as helping to shape its story.

But The Line’s narrative deserves much more than being boiled down to rehashed ideas from other text. Williams absolutely achieved his intent to break new ground in video gaming; to better convey the horrors and realities of war that are so glorified in games, and without any context forces gamers to truly think about their actions. The Line does that wonderful thing that all great stories do: it makes you think about it long after rolling credits. Except for this time, unlike in film and literature, it was the consequences of your own actions and your foolhardiness that are left rattling around your head.

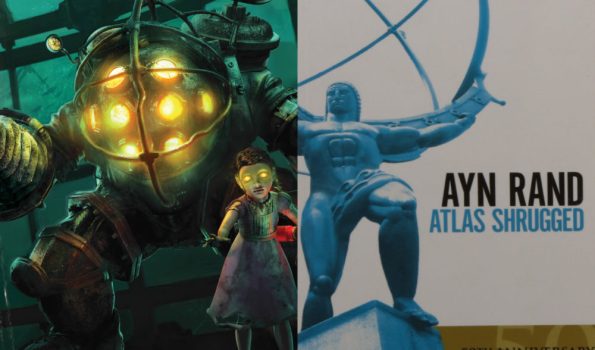

BioShock – Atlas Shrugged

The original BioShock is fondly remembered as one of gaming’s most compelling single-player experiences. The dark, dystopian world of underwater Rapture and its eerie inhabitants make for a superbly atmospheric setting, and it’s given context by an absolutely brilliant narrative that twists and turns in a way that left us dumbstruck. In fact, it’s that very famous deception that gave rise to games like Specs Ops: The Line. Importantly, it helped pioneer the notion that players didn’t always have to play the triumphant heroic role to be successful.

BioShock is the story of a utopia fallen, a once prosperous independent society destroyed by their obsession over a substance called ADAM, and steered to their downfall by a tyrant who rules them. Fans of dystopian works of fiction will have noted similarities to literary works such as George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four and Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. Levine himself certainly acknowledges them as inspiration. But it’s Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged that might be its greatest inspiration, though not necessarily in a conventional way.

Like BioShock, Atlas Shrugged depicts a grim world, but its own segregated super-city is one of utopia and success. The plot moots that society can exist in isolation from the evils of oppression, prospering as a capitalist under the control of a visionary, named Ayn Rand. So Ken Levine’s BioShock shares a thematic premise, but it’s actually the ultimate riposte to Rand’s theory. For Levine, capitalist societies can’t self-govern according to philosophies of reason and individualism. Speaking to Techcrunch, he said:

“What I was trying to do with BioShock was to say, ‘Okay, well, [in Atlas Shrugged] that’s a utopia where Ayn Rand, who made the philosophy, made all the rules, and all the characters were under her control. What if things weren’t under everybody’s control?’ And I think that’s the problem with utopias — we bring ourselves to it, you know? We think we’re leaving our problems behind but – I don’t mean this in a cynical way – we are the problem. Like, whatever social problems that occur come out of us. It’s not like they fall out of the sky. I think people think they’re going to go to a utopian society, and I think it’s not really possible.”

You’ll notice that Atlas Shrugged protagonist Ayn Rand and BioShock antagonist Andrew Ryan share similar names. Ryan is Rand, except in BioShock, instead of doggedly sticking to idealist philosophy, he’s vulnerable to human nature. In other words, Levine considers that in actuality, humans don’t respect honor or greatness, and they’re happy to use violence even when they aren’t actually threatened themselves.

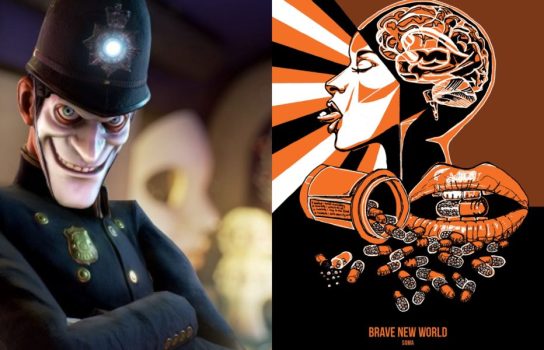

We Happy Few – Brave New World

Rather like BioShock, Compulsion Games’ We Happy Few depicts a dystopian society of the 1960s. And also similarly to BioShock, it’s heavily inspired by the iconic novel Brave New World.

Huxley’s Brave New World details a society that adheres so rigidly to a strict class system that their genetic traits are artificially manipulated so that they fall into categories from birth. The result is a class-conditioned utopian society, utterly brainwashed by psychological manipulation. Void of any real ability to feel emotion, society is administered a drug called Soma, which helps them to feel happiness, and keeps them under control.

We Happy Few incorporates all of the major themes tackled by Huxley’s work. Joy, the happy drug that inebriates the people of Wellington Wells, is one obvious starting point. But there are other major themes that are all on display quite vividly, too.

For one, the way in which violence and sex are perceived and represented. In Brave New World, the population, high on Soma, believe violence not to exist. Sex, on the other hand, is largely taboo, to be handled in a regulated and orderly manner. The Feelies, for example, is the name given to a theater where the population is able to experience pleasure in a controlled fashion. Lust and passion don’t exist among these peoples removed from normal human nature, and it warps their perception of normal behavior. In the same way, for citizens of We Happy Few’s Wellington Wells, violence also doesn’t exist, simply because it’s actually their form of entertainment, spurred on by the effects of Joy. Sex, meanwhile, isn’t even mentioned.

More than just Huxley’s Brave New World, We Happy Few draws on other popular British literature such as Clockwork Orange and V for Vendetta. It also weaves social problems affecting our own contemporary society into its overarching story to produce something of a satire about many of the issues with consumerist and capitalist lifestyles. Narrative director Alex Epstein said in an interview, “We Happy Few is inspired by, among other things, prescription drug culture — the idea that no one should have to be sad if they can pop a pill and fix it. It’s also about Happy Facebook culture: no one shares their bad news because it would bring everyone down. As a culture, we no longer value sadness.”

Republique – 1984

I’ve written this entire list so far without saying the word “Orwellian,” which I tend to do repeatedly when discussing video game dystopias. There’s good reason for that, of course: George Orwell practically fathered the dystopian literature genre. His classic novel Nineteen Eighty-Four details a society controlled by government surveillance and propaganda where individualism is persecuted. So famous is it, in fact, that much of the book’s lingo —thoughtcrime, doublethink, newspeak, big brother— are familiar terms entered into common usage when referring to any form of information-control or oppressive government. It’s also required reading for any dystopian video game. Perhaps most obviously, Republique.

Originally an episodic mobile game from Camouflaj, Republique was born out of developer Ryan Payton’s desire to “stop complaining about the lack of real games on mobile and start making one.” It later came to console, of course, but the themes of surveillance within the game were rather cleverly woven into the gameplay of the original the mobile version. The player actually controlled movement by instructing its protagonist to move around via the surveillance cameras. And you were, of course, holding a surveillance device in the palm of your own hand as you played.

For fans of Orwell’s seminal novel, Republique’s announcement understandably had them excited. It looks like the ultimate totalitarian state, led by a sinister “Overseer,” with a population totally censored from the outside world, living in perpetual paranoia and brainwashed by the crazy ideology of their dictator. No surprises, Nineteen Eighty-Four was the game’s biggest influence, with Payton admitting the development team was “obsessed with dystopian societies” and were wanting to design a game about contemporary societies real-life movement “into this world that Orwell described and warned us about.

If you haven’t played Republique and you’re a fan of dystopian fiction, I highly recommend you do so. The gameplay isn’t especially exciting, and the movement often clunky, but the Metroidvania-like exploration and the incredible detail of the underground facility known as Metamorphosis, which houses the Overseer’s “utopia” is absolutely worth experiencing.

Wolfenstein: The New Order – The Man in the High Castle

One of gaming’s most precious franchises, Wolfenstein stands next to Doom as one the most seminal FPS games ever made. The original 1981 PC game was actually inspired by a work of fiction itself, The Guns of Narvone by Alistair MacLean, which tells the tale of a squad of British troops assaulting an impregnable German-held castle in the Greek islands. Fast forward over 30 years and seven games, however, and Machine Games’ reboot, Wolfenstein: The New Order, sees the franchise explode back into the industry spotlight with a very different narrative premise.

The New Order’s opening prologue sees the Nazis win WWII, forcing the Allies to surrender after their last-ditch effort to overcome the regime’s superior technology and weaponry. And as the game begins-proper, we’re presented with a dystopian 1960 USA ruled by the Nazi party. The swastika replaces the stars of the American flag, and Nazi architect Albert Speer’s vision of massive Nazi cities stand proudly atop ruined American ones —it’s Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle brought to life.

Of course, Wolfenstein injects its own unique —and eccentric— sci-fi flavor with over-the-top robots and crazy futuristic weaponry, but the parallels of its themes are certainly inspired from the classic American novel. The game explores that terrifying “what if?” question that arises whenever we contemplate the terrifying implications of losing WWII to the Axis forces. It depicts a society ruled by censorship, oppression, and racism in the same way as Dick’s famous novel. And though Wolfenstein’s team of ass-kickin’ protagonists are practically fantasy heroes in comparison to the beaten, terrified, and desperate characters as in Dick’s work, they both represent resistance fighters determined to fight back against oppression.

Updated: Aug 22, 2018 03:10 pm